Crises of American Capitalism

“ The executive of the modern state is nothing but. a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie [i.e. capitalist ruling class].” Karl Marx

Image: © George Kallas

Thus, in all class-divided societies throughout history, “political power is merely the organized power of one class for oppressing another.” (Berberglou 24) Class Structure and Social Transformation. (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1994)

America is a Capitalist Republic and Not a Democracy

Technically the United States has never been a Democracy, one will not find the term Democracy in the US Constitution.

Democracy is a combination of the Greek words Demos ("the people") + kratein ("to rule") = Rule of the People.

The term Democracy does not appear in the US Constitution.

In fact, America is defined by this type of regime: Oligarchy

Two American Political Scientists Conducted Extensive Research from US congressional record and found that that US is an oligarchy of a few powerful elites and not a democracy:

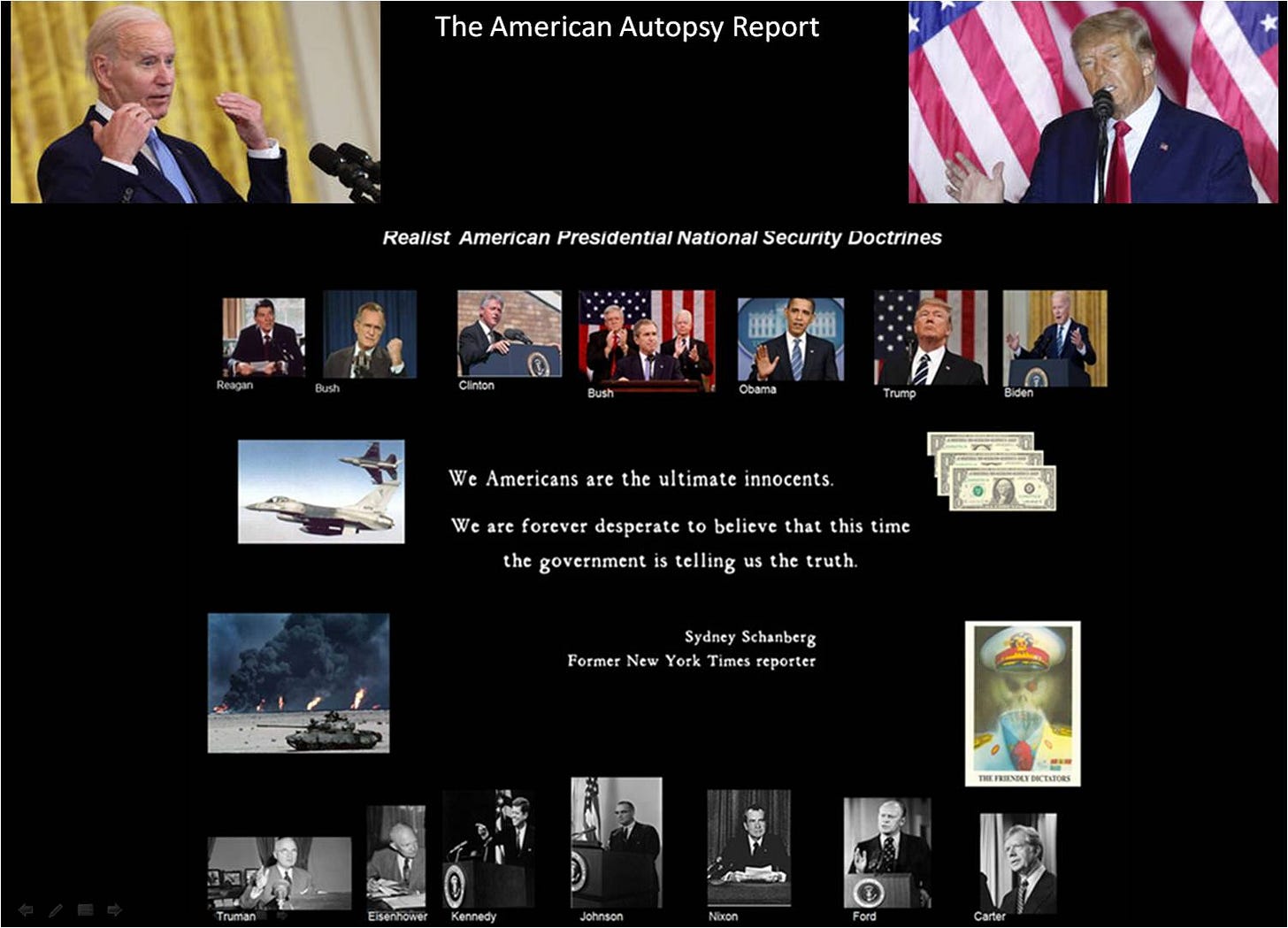

U.S. has become a major global tax haven. Capitalist Rich Thank "In God We Trust" America...$$$

Written by 55 of the richest white men, and signed by only 39 of them, the US constitution is the sacred text of American nationalism. Popular perceptions of it are mired in idolatry, myth and misinformation - many Americans have opinions on the constitution but have little idea what it says. This book examines the constitution for what it is – a rulebook for elites to protect capitalism from democracy. Social movements have misplaced faith in the constitution as a tool for achieving justice when it actually impedes social change through the many roadblocks and obstructions we call 'checks and balances'. This stymies urgent progress on issues like labour rights, poverty, public health and climate change, propelling the American people and rest of the world towards destruction. Robert Ovetz's reading of the constitution shows that the system isn't broken. Far from it. It works as it was designed to.

We the Elites: Why the US Constitution Serves the Few by Robert Ovetz | Goodreads

Why The US Constitution Is An Obstacle To Change

/

/ https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/60651294-we-the-elites

Crisis of American Capitalism - Class Warfare raging in America for generations yet Americans still worship rich capitalists while the rich laugh all the way to bank. American silence, passive and loyal to a system that threw them overboard years ago.

George Carlin describing facts about this plutocracy/Oligarchy

29 Dec, 2024 21:06

Russia Today

US homelessness hits new record

The number of homeless people in the United States has reached a record level since the federal government began tracking teh figures in 2007. According to data released this week, almost three quarters of a million people, 771,000 are homeless in America, an increase of 18% compared to 2023, marking the sharpest annual rise in decades.

The figure published by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) on Friday translates to approximately 23 out of every 10,000 people in the US. The increase follows a 12% rise in 2023, which the department attributed to skyrocketing rents and to the conclusion of pandemic assistance.

A severe lack of affordable housing nationwide is being compounded by “rising inflation, stagnating wages among middle- and lower-income households, and the persisting effects of systemic racism,” natural disasters, and an influx of migrants without access to stable housing, according to the HUD statement.

Median rent was up 20% in January 2024 from rent costs for the same month three years earlier, the National Low Income Housing Coalition wrote in March.

According to the HUD, there has been a 39% increase this year in the number of individuals in families with children who depended on shelters or slept outside. This amounts to approximately 259,000 people, the highest figure recorded since data collection began.

The report also shows that nearly 150,000 children were homeless on the targeted January night, a 33% increase from the previous year’s count. Meanwhile, the number of veterans experiencing homelessness declined by 8% from 2023.

The new homelessness figures come amid the Biden administration’s pledge to increase funding for affordable housing and expand services aimed at preventing homelessness. However, advocacy groups argue that more systemic reforms are needed, such as stronger tenant protections, rent controls, and a focus on mental health and addiction services.

The US Supreme Court ruled in June that cities may ban homeless residents from sleeping outside; more than 100 jurisdictions around the country have since taken steps in that direction, Associated Press writes.

On the campaign trail, then-candidate Donald Trump repeatedly pointed to illegal immigration as the cause of high housing costs, vowing that his plan to carry out “the largest deportation operation in American history” would lower home prices, as quoted by the New York Post. Immigration “is driving housing costs through the roof,” Trump said at a September rally in Arizona.

Source:

https://swentr.site/news/610174-number-of-homeless-in-us/

Just 1 in 3 US voters still believe in ‘American dream’ – poll

The portion of Americans who think anyone who works hard can get ahead in life has halved since last year

Just over a third of Americans (36%) still have faith in the so-called American dream, the idea that anyone can advance if they work hard, a Wall Street Journal-NORC poll published on Friday found. That’s barely half the percentage who responded affirmatively to a similar question last year, reflecting an increasingly bleak outlook for the US economy.

While 45% thought the American dream once held true but no longer did, 18% said it had never been true – more than double the percentage of respondents who had given the same answer ten years ago.

Belief in this idea, once central to the American identity, has seemingly plummeted since last year, when 68% of poll respondents agreed with a similarly-worded statement: “If people work hard, they are likely to get ahead in America.” However, a more modest 48% of those polled by another survey provider in 2016 still believed in the American dream, down from 53% in 2012.

Half of the respondents to Friday’s poll, conducted last month, said life in the US was worse than 50 years ago, while just 30% said it had gotten better. Half also agreed that the economic and political system was “stacked against people like [them],” while just 39% disagreed.

The percentage who saw themselves as a disadvantaged class held largely constant from last year, when 51% agreed with the statement “Often, I feel like I am one of the people the elites in this country look down upon” and 39% disagreed.

Age was a major predictor of belief in the American dream, with just 28% of those under age 50 having faith that hard work would get them ahead in life, compared to 48% of those over 65. Men were far more likely to have confidence in the power of hard work than women (46% vs 28%).

Despite this apparent disillusionment, respondents had a more favorable outlook on the economy than in two previous WSJ-NORC polls, with 35% rating it as “good” or “excellent” compared to just 17% who said the same in May 2022. Inflation has dropped from last year’s four-decade high, meaning Americans may be having an easier time making ends meet, though prices remain significantly higher than before the Covid-19 pandemic and other recent polls indicate the economy remains a major source of anxiety.

US President Joe Biden has struggled to shore up support for his reelection amid widespread perception he has mismanaged the economy. Over half of respondents to a Financial Times-Michigan Ross survey conducted earlier this month said they were financially worse off under Biden, while nearly half agreed the Democrat’s policies had hurt the economy.

America is a Capitalist Republic and Not a Democracy

Technically the United States has never been a Democracy, one will not find the term Democracy in the US Constitution.

Democracy is a combination of the Greek words Demos ("the people") + kratein ("to rule") = Rule of the People.

The term Democracy does not appear in the US Constitution.

In fact, America is defined by this type of regime: Oligarchy

Two American Political Scientists Conducted Extensive Research from US congressional record and found that that US is an oligarchy of a few powerful elites and not a democracy:

U.S. has become a major global tax haven. Capitalist Rich Thank "In God We Trust" America...$$$

Homeless and Hunger in America, Homeless World

Hunger in America

Making a Killing from Mass Homeless America

Bezos-Backed Company Surpasses $100M In Single-Family Home Acquisitions While U.S. Housing Shortage Worsens

Predatory Capitalism's Economic Inequality and Homelessness

Housing Shortage, Soaring Rents Squeeze US College Students – NBC Bay Area

Eric Risberg/AP

University of California, Berkeley freshmen Sanaa Sodhi, right, and Cheryl Tugade look for apartments in Berkeley, Calif., Tuesday, March 29, 2022. Millions of college students in the U.S. are trying to find an affordable place to live as rents surge nationally, affecting seniors, young families and students alike.

College students squeezed by a massive housing shortage and surging rents are paying too much for moldy apartments, commuting long distances or sleeping in their cars to get an education — and that doesn’t appear to be changing anytime soon.

For some colleges, the housing crunch was related to the pandemic, which muddied projections for who might want on-campus dorms when classes resumed in person last fall. But the lack of housing both on-campus and off has been a longstanding problem at other schools, including many in California, where homeowners and communities have sued to curb new student housing construction.

Tenants grapple with rent hikes amid overall inflation spike | AP News

Tenants grapple with rent hikes amid overall inflation spike

LOS ANGELES (AP) — At a time when rising gasoline and food prices are already straining Americans’ budgets, many apartment tenants are grappling with soaring rents.

The Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach metropolitan area in Florida saw overall median rent soar over 50% in April from a year ago, to $3,045 a month, according to Realtor.com.

The next biggest increase? The central Florida metropolitan area made up of Orlando, Kissimmee and Sanford, where the median rent jumped 32.9% from April last year to $1,927, the firm said.

Nationally the median rent climbed to $1,827, an increase of about 17% versus the same month last year, according to Realtor.com, which tracks rental listings in the 50 biggest U.S. metropolitan areas.

“The fact that rents are rising much higher than we’ve seen historically is a reflection of the unique time that we’re in, where the economy is adjusting to a couple of extraordinary years and shifts in preferences,” said Danielle Hale, Realtor.com’s chief economist.

National median rent has set new all-time highs for 14 months in a row. At the current pace of increases, it could hit $2,000 by August, Hale said. Rents as measured by the U.S. consumer price index haven’t risen this fast since May 1991.

In a recent survey of renters and landlords by Realtor.com more than 66% of tenants said higher rents were the biggest strain on their finances, while about 76% noted they’re unable to save as much money every month as they did a year ago.

Tenants are likely to see further rent hikes this year. About 72% of the landlords surveyed said they were planning to increase rents within 12 months.

Landlords have the leverage to ask for higher rents because demand is strong. Years of rising home prices and the recent surge in mortgage rates have left many would-be homebuyers with little choice but to keep renting.

Developers are responding by ramping up apartment construction to the fastest pace in decades.

Newly started construction of apartment buildings climbed to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 612,000 units in April, according to the Commerce Department. That’s up 42.3% from a year earlier and the fastest seasonally adjusted annual rate since April 1986.

That additional supply should help eventually, but it can take months or years for projects to hit the market, especially given supply chain and labor constraints that have delayed all manner of construction during the pandemic.

While the national homeownership rate is around 65%, there are more renters than homeowners in many large metropolitan areas, such as New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, Hale said.

And the burden of sharp rent increases tends to fall mostly on a segment of the population that tends to be younger and less financially flexible.

“The renter population tends to be different than the homeowner population,” Hale said. “They tend to be younger, they tend to have less wealth, and also be lower income, generally speaking, which can make it more difficult for them to navigate price increases.”

According to Monroe Group findings, with the U.S. minimum wage at $7.25/hour, a renter making that wage would need to work 90 hours per week to afford a one-bedroom rental home at the fair market rent and 112 hours per week to afford a two-bedroom.

Rent Surges on Single-Family Homes With Landlords Testing Market

“Companies are trying to figure out how hard they can push before they start losing people,” said Jeffrey Langbaum, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “And they seem to be of the opinion they can push as far as they want.”

Rents Soar for Millions of Americans as Threat of Eviction Looms

Rents are soaring in many U.S. cities as the economy rebounds, squeezing the budgets of tenants who also face increased risk of eviction after courts overturned a pandemic-era ban.

There’s no single indicator that captures a complex national picture, as Covid-19 drove major shifts in where people live and work. Still, data point to tight markets in much of the country.

The median monthly charge on a vacant rental jumped by $185 in March from a year earlier, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. A national index compiled by Apartmentlist.com shows that rents rose 1.9% in April alone, the most in data going back to 2017.

State of Homelessness: 2023 Edition - endhomelessness.org

Homelessness-and-Poverty-Fact-Sheet-Jan.-2022.pdf (familypromise.org)

Homelessness-and-Poverty-Fact-Sheet-Jan.-2022.pdf

Mission and Vision | Tenants Together

Tenants Together is a statewide coalition of local tenant organizations dedicated to defending and advancing the rights of California tenants to safe, decent, and affordable housing. As California’s only statewide renters’ rights organization, Tenants Together works to improve the lives of California’s tenants through capacity-building, movement-building, and statewide advocacy. Tenants Together seeks to support and strengthen the statewide movement for renters’ rights.

We believe that housing is a human right, not a commodity. We advance policy that is driven from tenant experience. To resist displacement we must organize renters and other allied groups to make strong and bold demands of those in power. Organizing for tenants’ rights to us means organizing tenant unions and building associations, building tenant power for the long-term. If we are to win the most transformative policy, we must center our movements around the leadership of those most affected: low-income communities and communities of color. We seek alignment with other movements fighting against structural oppression because tenants do not live single-issue lives, and the right to housing will only be won by building power with other movements. This includes, but is not limited to, movements that build collective power and are rooted in racial, gender, economic, environmental, and disability justice; trans and queer liberation, and indigenous sovereignty.

THE CALIFORNIA TENANT BILL OF RIGHTS | Tenants Together

#CancelRent California | Tenants Together

June 2023

Renters’ rights: California advocates chip away at landlords’ political influence, CalMatters

Rents soared 151%. Under California’s new law, tenants are getting a refund, CalMatters

April 2023

NYC real estate investor: The 'golden age' of landlords is over, Business Insider

Financialization and Inequality | Dollars & Sense (dollarsandsense.org)

By Arthur MacEwan | September/October 2022

Good-quality, safe, and affordable housing is fundamental to personal well-being and security. But for millions of U.S. families and individuals, paying today’s high housing costs means sacrificing on food, health care, savings, and other essential expenses.

—Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, The State of the Nation’s Housing 2018

Why? Why do millions of people experience housing problems? And in particular, why are hundreds of thousands of people in the United States homeless? At the beginning of 2022, there were 569,334 people on the streets or in shelters, according to the official “point-in-time” count (see sidebar, “Counting the Homeless”).

Homeless people are often portrayed as suffering from mental illness or some form of addiction. Indeed, estimates suggest that 20% to 25% of the homeless are mentally ill and as many as 50% are dependent on alcohol or other drugs. Also, some 40% of the homeless are African Americans. These numbers, however, while telling us who is homeless, do not tell us why they are homeless. (Moreover, with substance dependence, homelessness may be a cause rather than the effect; while mental illness has complex causes, homelessness may bring out the illness.)

Counting the Homeless

“Point-in-time” (PIT) counts are the basis for formal, government estimates of the number of homeless people in the country. PIT counts are unduplicated one-night estimates of both sheltered and unsheltered homeless populations. The one-night counts are conducted by Continuum of Care (CoC) organizations nationwide and occur during the last week in January of each year. A CoC organization is a regional or local planning body that coordinates funding for housing and services for homeless families and individuals.

Critics of the PIT count tend to see it as providing an underestimate of the homeless. Advocates and service providers argue that scheduling the event in the winter creates an undercount. “The count is during the winter early in the morning, when it’s harder to actually find folks because they’re seeking some sort of refuge. They want to stay out of sight in general for their own safety,” Kelley Cutler, the human rights organizer at the Coalition on Homelessness, told a Bloomberg reporter. Margaretta Lin, the executive director of the Dellums Institute for Social Justice, told the same reporter:

We know there’s an epidemic, right? You would have to be blind to not understand the nature of the epidemic. But HUD [the Department of Housing and Urban Development] defines homelessness as people who are literally homeless. People who are in a motel for that night or couch surfing for that night, under the HUD definitions, they are not considered homeless. In any case, with small teams of counters riding and walking the streets in the wee, dark hours of the morning, any number of homeless people “on the streets” are bound to be missed.

Sources: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress,” January 2021 (huduser.gov); National Alliance to End Homelessness, “What is a Continuum of Care?,” January 14, 2021 (endhomelessness.org); Alastair Boone, “Is There a Better Way to Count the Homeless?,” Bloomberg, March 4, 2019 (bloomberg.com).

Foundations of Homelessness

Surely, a good part of the why lies in economic problems—such as poverty, high housing costs, and inadequate public social-support systems. This agglomeration of problems is, in turn, a manifestation of the high degree of economic inequality in the United States. Inequality works directly and through the political process to cause homelessness.

As the economy grows and overall income rises, the demand for housing grows as people want more living space. The rising demand tends to push up the price of housing. The supply of housing tends to respond slowly and perhaps not fully to the rising price (the supply is relatively “price inelastic”). The result is a rising house-cost burden across the board. If income grows evenly across all segments of the population, the rising prices of housing (purchases and rents) is no more of a problem for people with low incomes than it was previously.

However, when the income growth is unequally distributed, with a larger share of the growth going to the top and a lesser share, perhaps none, going to those at the bottom, the burden of housing costs is proportionally larger for those at the bottom. Furthermore, those at the top, with their increasingly large share of the income increase, drive up the price of housing beyond what it would be if the income rise were equally divided.

There is, moreover, a widely perceived shortage in the overall supply of housing. Often, this alleged shortage is attributed to “excessive regulations,” parts of which are regulations that prevent public, or simply low- cost, housing in wealthy suburbs. (Unfortunately, while some of these regulations are elitist or racist or both, the efforts to eliminate them feed into the conservative anti-regulation ideology.) The “shortage,” however, is not so much an overall shortage but a shortage of low-cost housing. In the early 1980s, 40% of new homes were “entry-level” homes (i.e., homes of less than 1,400 square feet); by 2020, the figure had dropped to less than 10%. This phenomenon suggests that home builders were increasingly finding it unprofitable to build homes for people with low incomes—that is, the large share of the population whose incomes have been relatively stagnant as income inequality has risen.

And one more sign of the problem with declaring a housing “shortage”: The National Association of Home Builders reports that in 2020, roughly 7.1 million homes, 5.1% of the U.S. housing stock, were second homes. Yet, according to the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, the “housing supply deficit” in 2020 was 3.8 million units, 2.7% of the number of households.

Behind the housing “shortage,” then, is the high degree of economic inequality. New construction tends to increasingly take the form of homes destined for the rich, and the new construction of other levels of housing, especially affordable housing, is limited. People whose incomes are high but who are not among the rich, and who in an earlier period might have occupied homes in expensive neighborhoods, are forced to look for homes in the next level down. And this process of shifting locations continues on down the scale. The visible impact is gentrification.

At the bottom of this process, some people simply get pushed out of the housing market entirely. They become homeless. This push-out pressure, however, doesn’t affect all low-income people in the same way. Those who have other difficulties—e.g., experiencing mental illness, addiction, health problems, or racial discrimination—are less able to cope. So, they appear disproportionately among the homeless.

To sum up this direct effect of rising inequality: The rising incomes of the rich drive up the cost of housing while the incomes of the poor are relatively stagnant.

In addition to these direct economic impacts of inequality on homelessness, the political process has worked in the same direction. One of the consequences of the political power of the wealthy, enhanced as their share of income rises, is the intensification of the opposition to tax increases and government spending on social programs. This direction of government policy rose sharply during the Reagan administration and has been maintained since, in both Republican and Democratic administrations (for example, in the attack on social welfare programs under President Bill Clinton).

The impact on support for the housing safety net has been substantial. For example, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies (quoted above), since the late 1980s, the

number of very low-income families has soared by six million, to more than 19 million. At the same time, federally subsidized rental housing has increased by only 950,000 units while the low-cost stock (with rents under $800 in real terms) has shrunk by some 2.5 million units.

Although poverty and homelessness have increased in recent decades, government spending has shifted to other priorities. According to a 2017 study by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, 75% of low-income, at-risk renters were not receiving federal assistance.

Empirical Evidence

Empirical support for the inequality-homelessness connection is provided in a recent study published in the January 2021 issue of The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. The article is titled “A Rising Tide Drowns Unstable Boats: How Inequality Creates Homelessness.” The authors of the study focus on the fact that homelessness varies substantially among communities across the country. They use a sample of 239 communities with populations above 65,000. Taking account of other factors (e.g., the average level of income in the communities and the existence of social-support programs), they examine the inequality-homelessness relationship over a 12-year period (2007 to 2018).

Their results are quite clear (statistically significant) in demonstrating the correlation between income inequality and homelessness (measured as a share of the population). The authors conclude that income inequality is an “important driver of increases in homelessness.” In particular, their results suggest that for a city of 740,000 (the average size of communities in their study), an increase of local income inequality that is the same as the average for the whole United States between 2007 and 2018 “translates into roughly 200 additional people who are homeless in that community on a given night.”

The statistical correlation between inequality and homelessness does not “prove” that greater inequality causes more homelessness. The authors of the study, however, undertake additional statistical analyses that support the argument that inequality is a cause of homelessness. Moreover, the authors provide a strong and reasonable explanation supporting causation (drawn on in the discussion above).

Other Factors

Nonetheless, there are other factors that also cause homelessness. For example, in examining the inequality-homelessness connection, the authors of “A Rising Tide Drowns Unstable Boats” take account of the extent to which a community provides permanent housing for people who have been homeless; this permanent housing is measured in terms of permanent supportive housing (PSH) units. Not surprisingly, more PSH units in a community yield less homelessness at any of the degrees of income inequality.

Also, the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill (moving people out of large psychiatric hospitals and subsequently closing many such facilities) in the second half of the last century was not accompanied by sufficient funding and creation of smaller, local facilities and support programs for people with psychiatric difficulties. Many of these people became homeless. It is, then, not mental illness or deinstitutionalization that causes homelessness, but the lack of this support that puts people on the streets or in shelters. Of course, this lack of support for the social safety net, as has been suggested above, is in part a consequence of rising inequality. (For a review of the history of deinstitutionalization and its aftermath, see John Summers, “The Group Home Racket,” D&S, November/December 2021.)

The creation of more PSH units and more extensive support for the mentally ill could reduce homelessness. In the context of a high degree of economic inequality, however, the impact of such programs may be minimal; and the high degree of economic inequality is likely to limit the creation of such programs.

The economic pressures that have grown in the United States in recent decades have generated the burdens on low-income people that make some of them homeless. Many low- income people are able to cope, even under these pressures. Those less likely to be able to cope are people with the conditions of psychiatric difficulties, suffering addictions, or facing racial discrimination. They are the ones who disproportionately become homeless. These conditions determine which people are more likely to be homeless. But it is economic pressures, with income inequality at their center, that cause homelessness.

ARTHUR MACEWAN is professor emeritus at UMass Boston and a Dollars & Sense Associate.

Institutional Homelessness & Discrimination in

American Capitalist Housing Markets

Housing crisis unaffordability must be understood as a core feature of economic inequality.

According to the Monroe Group, which publishes national housing statistics, not one county in the U.S. can meet its low-income population’s need for safe, affordable housing. Reuters reports that housing prices are rising at twice the rate of inflation and income. According to “The State of the Nation’s Housing,” an annual study released by the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, housing affordability for renters is worsening, as rent increases are outpacing income gains, especially among minority renters.

According to the study, in 2019, 20.4 million renter households paid more than 30% of their income toward housing, qualifying them as cost burdened. In the same year, more than 80% of households with incomes of less than $25,000 were at least moderately cost burdened, and 62% of them were severely cost-burdened, paying more than half of their monthly income towards housing.

Rising rents, combined with a tight supply—The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that for every 100 low-income renters, there are only 57 affordable units available—have increased pressure on moderate-income households as well, "lifting the share of cost burdened households earning between $25,000 and $49,999 from 44% in 2001 to 58%" in 2019.

https://www.statista.com/chart/6949/the-us-cities-with-the-most-homeless-people/

Capitalist Housing Crisis: American Working Class Renters Hard Hit

Surging Rents Push More Americans to Live With Roommates or Parents

Apartment demand in the third quarter was lowest of any quarter since 2009

After a long stretch of record-high rents, Americans are renting fewer apartments as demand in the third quarter fell to its lowest level in 13 years.

Some renters are choosing to take on roommates, while others are boarding with family or friends. More people are opting to stay longer in their parents’ homes or moving back in, rather than pay steep rent increases, according to a recent UBS survey.

Apartment demand in the quarter, measured by the one-year change in the occupancy of units, was the lowest since 2009, when the U.S. was feeling the effects of the subprime crisis, according to rental software company RealPage. Measured quarterly, the drop in demand was the worst of any third quarter—normally prime leasing season—in the more than 30 years RealPage has compiled the data.

Meanwhile, the apartment-vacancy rate rose to 5.5% in the third quarter, up from 5.1% the quarter prior, according to property data firm CoStar.

Rents have risen 25% over the past two years, according to rental website Apartment List, pushing many renters beyond what they can now afford. Meanwhile, inflation on other essential goods, such as food and energy, is also eating into how much people have left to spend on housing.

“It’s a signal that rent can’t continue at the same level it has sustained over the last couple of years,” said Michael Goldsmith, an analyst at UBS. “We’ve reached a point where renters are maybe willing to pull out of the market.”

The apartment rental market looks to be cooling following a boom that started in early 2021. After the introduction of a Covid-19 vaccine, many people—especially younger people who had been living with their parents—rushed to rent in cities around the country. That boosted apartment demand and put upward pressure on rents. Some rental apartments were even subject to bidding wars.

Record high housing prices also played a role. They priced out many Americans who wanted to buy starter homes but instead have remained captives of the rental market. Home prices are now falling on a monthly basis, however, according to the latest S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller National Home Price Index.

Shonda Austin, a home healthcare worker, and her three children moved into her mother’s house in Flint, Mich., this month after facing a 24% rent increase in Las Vegas. She hopes to return to a home of her own by March to somewhere more affordable, such as Arkansas or North Carolina, where she could potentially buy.

“My goal is to just save as much as I can,” Ms. Austin said.

Rents have risen 25% over the past two years, pushing many renters beyond what they can now afford. Photo: Allison Dinner/Getty Images

The supply of new apartments, which has grown this year in large markets such as Phoenix and Dallas, may be contributing to the drop in overall demand, because new projects add empty units to a slowing market. Economic uncertainty rooted in fears of a recession may also be contributing to lower apartment demand.

Leasing also typically eases during colder months, but analysts said the drop in demand that started earlier this year is now greater than what was expected.

“The spring and summer leasing season was a total bust,” said Jay Lybik, national director of multifamily research at CoStar.

Yet even with the recent decline in demand, asking rents have remained near record highs. Nationally, asking rents have started to drop only slightly month-to-month, and are still up by 6% or more when viewed annually, according to several data sources. In some hot markets, they are up much more than that. In Charleston, S.C., rent is 14% higher than it was a year ago, according to Apartment List.

To escape record high prices, more people are choosing to live rent free with friends or family, a September UBS survey found. Eighteen percent of U.S. adults surveyed said they had lived rent free with other people during the last six months, up from 11% at the same time one year ago. That was the highest share of adults living rent free with friends and family since UBS began asking the question in 2015.

Other renters are finding roommates or splitting rent with family members. In North Charleston, S.C., 27-year-old bartender Bailey Byrum said her younger sister moved in with her at her two-bedroom rental house. Ms. Byrum said her sister had trouble finding her own place and had recently been living with her parents.

“She has a good job… but places by yourself are like $500 to $600 out of her budget,” Ms. Byrum said.

Jonathan and Kim McCann, of Birmingham, Ala., moved when their landlord wanted to sharply raise their rent. Photo: Kim McCann

Some landlords are encountering resistance to steeper rent increases. In downtown Birmingham, Ala., last year, Kim McCann and her husband leased a spacious loft apartment for $2,800, a rent that then already seemed overpriced, Ms. McCann said. This July the landlord texted Ms. McCann to say she would be raising the rent by an extra $900 a month because local real-estate demand had “exploded.”

Rather than pay $3,700 for the same apartment, Ms. McCann and her husband decided to move out in August. The loft sat on the market until at least this week, according to a listing on Zillow, and the asking price was cut twice.

Surging Rents Push More Americans to Live With Roommates or Parents - WSJ

Rents reach 'insane' levels across US with no end in sight | AP News

Krystal Guerra’s Miami apartment has a tiny kitchen, cracked tiles, warped cabinets, no dishwasher and hardly any storage space.

But Guerra was fine with the apartment’s shortcomings. It was all part of being a 32-year-old graduate student in South Florida, she reasoned, and she was happy to live there for a few more years as she finished her marketing degree.

That was until a new owner bought the property and told her he was raising the rent from $1,550 to $1,950, a 26% increase that Guerra said meant her rent would account for the majority of her take-home pay from the University of Miami.

“I thought that was insane,” said Guerra, who decided to move out. “Am I supposed to stop paying for everything else I have going on in my life just so I can pay rent? That’s unsustainable.”

Guerra is hardly alone. Rents have exploded across the country, causing many to dig deep into their savings, downsize to subpar units or fall behind on payments and risk eviction now that a federal moratorium has ended.

In the 50 largest U.S. metro areas, median rent rose an astounding 19.3% from December 2020 to December 2021, according to a Realtor.com analysis of properties with two or fewer bedrooms. And nowhere was the jump bigger than in the Miami metro area, where the median rent exploded to $2,850, 49.8% higher than the previous year.

apnews.com-Rents reach insane levels across US with no end in sight.pdf

OLIGARCHY 1. government by the few; 2: a government in which a small group exercises control especially for corrupt and selfish purposes; also: a group exercising such control ; 3: an organization under oligarchic control [Websters]

1: government by the wealthy; 2: a controlling class of the wealthy; Greek plouto+kratia, from ploutos wealth+kratia rule

George Carlin's comments describing facts about American plutocracy/oligarchy ].

PLUTONOMY

1: n. An economy that is driven by or that disproportionately benefits the wealthy few, or where the creation and control of wealth is the principal goal.

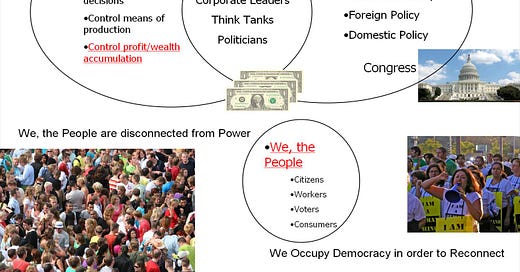

Corporate and state power combine economic and political power to use money as a weapon

― John Perkins, former "Economic Hitman"

Confessions of an Economic Hit Man: How the U.S. Uses Globalization to Cheat Poor Countries Out of Trillions

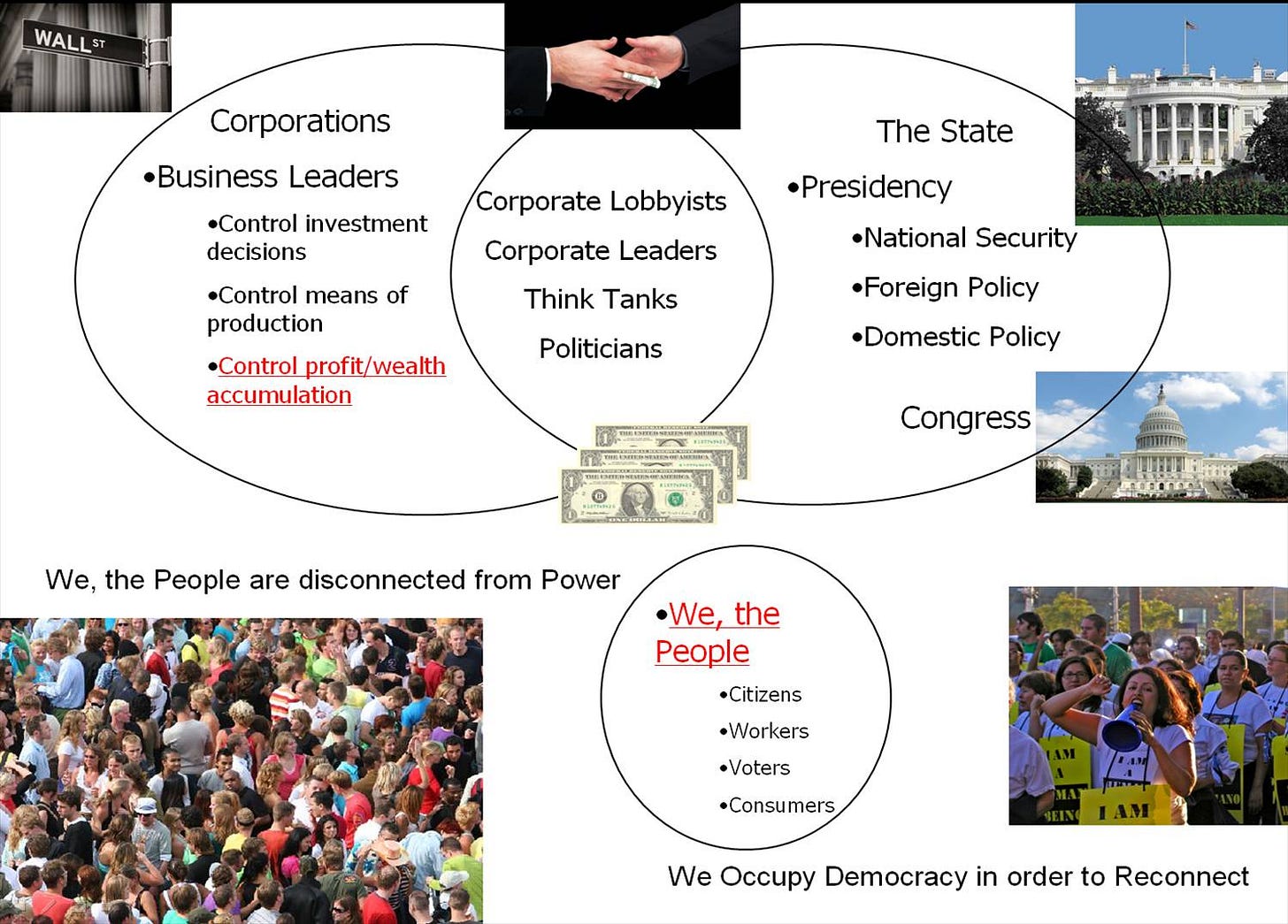

See also: Why the US is corporate capitalist national security state empire vs. a “Democracy.” US Wars are Good Business for American Capitalist Elites.

U.S. National Security State Imperialism Interference and Exploitation (substack.com)

https://nationalpriorities.org/cost-of/

Total Cost of Wars Since 2001Links to an external site. Every hour, taxpayers in United States are paying $32.08 million for Total Cost of Wars Since 2001.

The History of the US Capitalist Republic and Why it has never been a Democracy…. to be continued……

It’s a colossal read but entertaining . The American way has a sound: Kachang!